Joseph, a smallholder sugarcane farmer in Swaziland, stopped contributing to his funeral insurance cover – preferring to rely on his neighbours in the event a death in the family occurred. Questioned about this, it became clear that his decision boiled down to trust; “I just don’t trust the insurance business,” he said.

But what led to this mistrust in insurance? Joseph had witnessed an instance in which a funeral insurer failed to pay out the promised amount upon the death of its policyholder (a neighbour of Joseph’s). Despite the holder faithfully paying their premium for over 20 years, the insurance company only paid out a minimal amount in small instalments when he died. This led to Joseph’s conviction that “they [insurance companies] don’t deliver on their promises,” and this erosion of trust drove him out of the formal insurance system entirely.

The above example illustrates that trust is a powerful driver of human behaviour and a significant element of relationships. We trust our employer to pay us at the end of the month, so we go about our work as normal. We trust our friends to not gossip about personal, confidential matters, so we confide in them.

Trust is equally significant in the financial services industry. Financial service providers (FSPs) must first earn the trust of potential customers to ensure that they take up a product or service. But, it does not stop there – maintaining this trust and instilling confidence in customers is important for the sustained usage of products and services – and we identified in previous research that it is usage rather than take-up that is necessary for beneficial financial inclusion outcomes and impact of financial services.

Trust implies that there is an element of risk (as there is potential to lose something) as well as expectation (as we rely on the person, product or service to perform a particular action). This is relevant in financial services, as consumers entrust their money to FSPs with the expectation that it gives them back their money when requested; pays out an insurance claim when a risk happens; transfers money to another consumer or organisation when requested or gives them fair access to loans when an unforeseen expense occurs.

Although trust is a self-reported driver of (financial) behaviour, it is a complex construct. Many understand intuitively what trust is, but FSPs are possibly less sure of how trust is built or eroded.

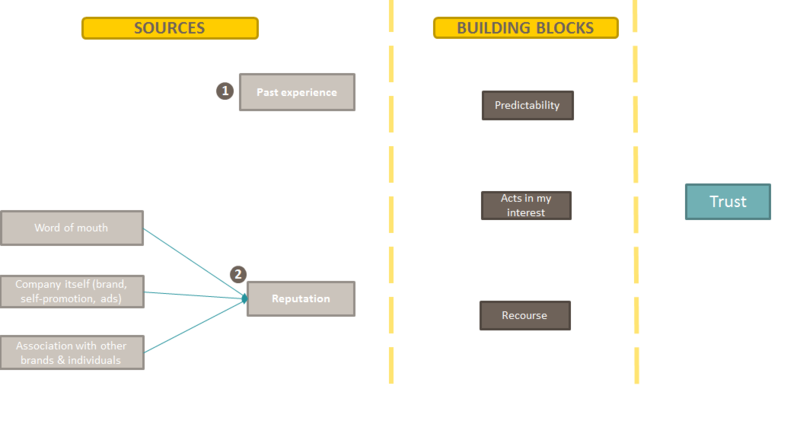

Through a review of literature in fields ranging from psychology, sociology and through to economics and marketing, and by drawing on qualitative research conducted during past projects, we have identified two sources of trust and three main building blocks that either help to build or erode trust.

Sources of trust

Past experience is one of the most valued sources of information when it comes to trust. However, just as positive past experiences with FSPs can build trust, negative ones can erode it. A bad experience at a bank will impact a consumer’s willingness to engage with this institution and use its products and services in the future.

Reputation has an influence on the way an organisation is perceived, which in turn affects trust. We have identified three main channels that affect the reputation of FSPs.

- Word of mouth: As consumers give weight to the recommendations of others, word of mouth has the power to drive consumers in or out of the formal financial system. In Tanzania, several customers cited the fact that their friends had posted about it on Facebook, as their reason for downloading and using the mobile-based credit lending app from Branch.

- Promotion of product, service or brand by the FSP itself: The way a service or brand is portrayed though advertising can be just as powerful as hearsay. For example, a mobile money service in Thailand found that using aspirational imagery in an advertisement actually alienated future users as they attributed the service as being for “business people” rather than people like them.

- Associations with other brands or individuals: The brands or companies a particular FSP associates with can influence its reputation. For example, one Branch customer emphasised the importance of partnering with a trusted third party that had a good reputation: “Once I found that Branch was having a payment number on Vodacom M-PESA menu, I was gain confidence of using their service. To my experience and knowledge, only trusted companies may have their payment number on Vodacom M-PESA menu.”

Building blocks of trust

If the primary sources through which trust are built are past experience and reputation, what are the underlying factors that affect the extent to which consumers trust financial devices or providers? We have identified several building blocks of trust and classified them according to three categories:

- Predictability: The extent to which consumers can predict the future actions of providers and devices impacts consumers’ levels of trust. Predictability is created by consistent, transparent and competent behaviour and, if the provider or device is perceived as predictable, it is likely the consumer will believe that they can more accurately forecast whether the provider will indeed deliver on what they expect.

- Acting in consumers’ interests: The perception that the provider is acting in the interest of the consumer will affect the intention to continue using the product. While predictability is based on reliability, transparency and competency, acting in the interest of the consumer is based on perceived motives as well as competency.

- Recourse mechanisms: If the provider of the device does not fulfil the action that the consumer expects, it is imperative that the consumer believes a viable channel of recourse is available to them. Recourse, in this sense, is not legal action per se, but rather whether the consumer knows what to do or who to confront when the provider is not acting in his/her interest and/or not fulfilling its promise. Recourse mechanisms reassure consumers that their money is safe and that they can resolve issues that arise.

We believe that when forming the intent to use a specific financial device, consumers look beyond the typical cost-benefit analysis of using the device, and also rely on rational, emotional considerations such as trust. We are conducting conceptual research to better understand the most significant drivers of usage of financial devices and how these interact and influence one another.

The conceptual research forms the backbone of the guide we are designing to help policymakers and FSPs identify which drivers are the most influential in determining usage within their given context. Our guide will identify which data types and collection methodologies are best suited to measure each driver identified in the conceptual model. For example, demand-side methodologies such as surveys, conjoint analysis, focus group discussions or human-centred design might be the best techniques to measure trust. We will continue to explore these techniques in more detail in our upcoming research.

We would love to hear from you if think we have overlooked a source or building block of trust, or if you have previously conducted research in this field. Please email kate@i2ifacility.org to contribute to our work on the drivers of usage. See more resources on establishing trust in the financial sector.